Philip Tilden (1887-1956)

Born in the later part of the Victorian era Philip Tilden was the son of William Tilden a professor and renowned chemist (who first synthesized rubber). William would send Philip to the newly formed Bedales School. A progressive school and arguably one of the first truly modern schools in Britain founded and run by John Haden Badley. Badley, after being heavily influenced by William Morris during his time at Cambridge, would become a lifelong socialist and proponent of the ideas of the arts and crafts lifestyle.

At Badley’s co-educational school students spent their time in the fields working as well as boys learning tailoring and cookery all of which were revolutionary ideas at the time. This early influence would have undoubtedly helped form Philip Tilden's ideas on what British architecture and gardens should look like as later in life he would say “Britain was not the home of the Acanthus and Cypress – it is the home of the Gothic Rose, the Oak, the Ash, and the Parasitic Ivy”.

After his time at Bedales Philip attended Rugby before starting his architectural career under the tutelage of Thomas Edward Collcutt (who had worked alongside Norman Shaw). After completing his training with Collcutt the two would briefly form a partnership. In 1917 Philip would start his own practice and gain the commission of restoring and refurbishing Allington Castle, Kent for Sir Martin Conway. When they first viewed the dilapidated castle Sir Martin and his wealthy American wife are quoted to say “We must have it” and would have Philip carrying out works there until 1933.

After his time at Bedales Philip attended Rugby before starting his architectural career under the tutelage of Thomas Edward Collcutt (who had worked alongside Norman Shaw). After completing his training with Collcutt the two would briefly form a partnership. In 1917 Philip would start his own practice and gain the commission of restoring and refurbishing Allington Castle, Kent for Sir Martin Conway. When they first viewed the dilapidated castle Sir Martin and his wealthy American wife are quoted to say “We must have it” and would have Philip carrying out works there until 1933.

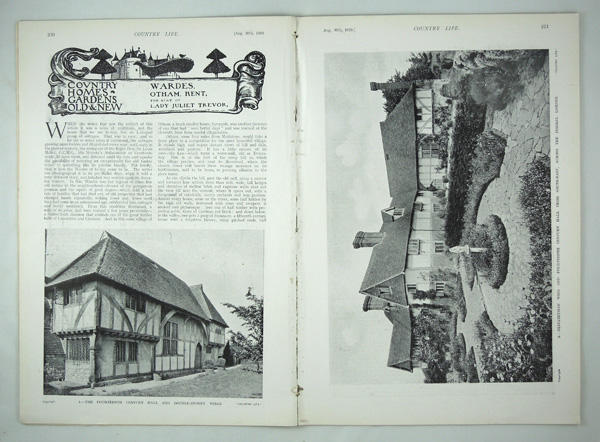

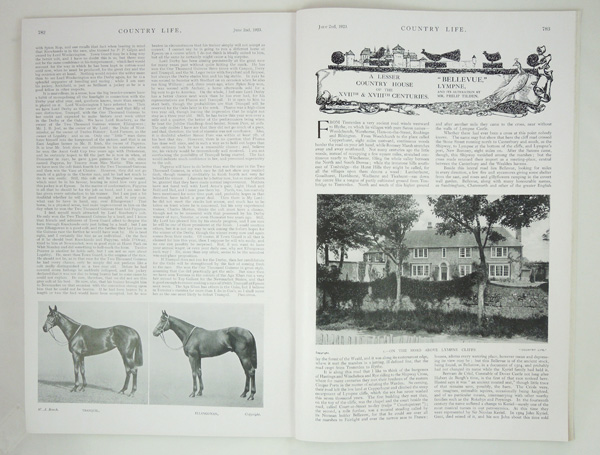

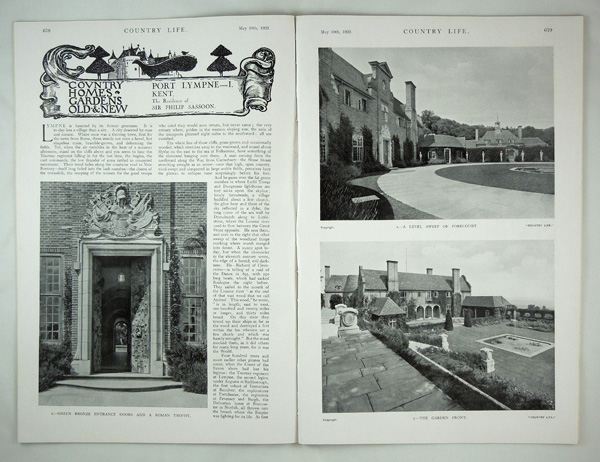

Philip Tilden's work at Allington would attract the attention of Sir Louis Mallet who employed him to provide interiors for Wardes (Otham Manor, as it is now known) and also introduce him to Sir Philip Sassoon. This introduction would be the most important of Tilden’s career, not just because of the commissions of Port Lympne and Trent House but of the connections that he would make thereafter.

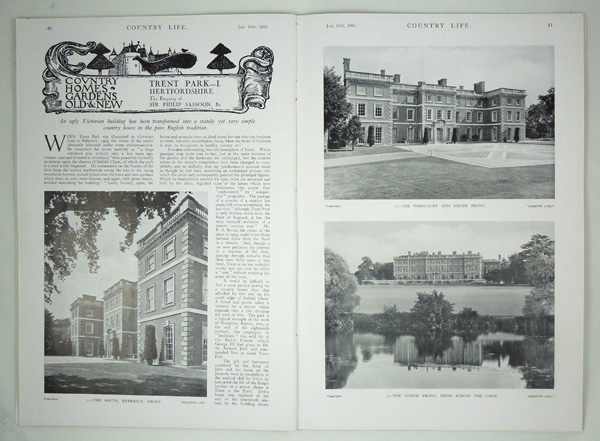

After completing the “Pleasure Palace” of Trent House, Sassoon, possibly seeing something of himself in Tilden, would make him part of his social circle. Robert Boothby wrote in his autobiography of seeing Philip at the parties at Trent House “a dream of another world – the white-coated footmen serving endless courses of rich but delicious food, the Duke of York coming in from golf… Winston Churchill arguing over the teacups with George Bernard Shaw, Lord Balfour dozing in an armchair, Rex Whistler absorbed in his painting… while Philip himself flitted from group to group, an alert, watchful, influential but unobtrusive stage director – all set against a background of mingled luxury, simplicity and informality, brilliantly contrived”.

After completing the “Pleasure Palace” of Trent House, Sassoon, possibly seeing something of himself in Tilden, would make him part of his social circle. Robert Boothby wrote in his autobiography of seeing Philip at the parties at Trent House “a dream of another world – the white-coated footmen serving endless courses of rich but delicious food, the Duke of York coming in from golf… Winston Churchill arguing over the teacups with George Bernard Shaw, Lord Balfour dozing in an armchair, Rex Whistler absorbed in his painting… while Philip himself flitted from group to group, an alert, watchful, influential but unobtrusive stage director – all set against a background of mingled luxury, simplicity and informality, brilliantly contrived”.

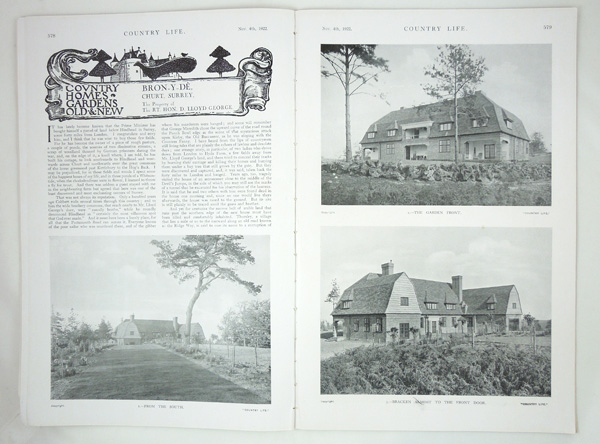

These gatherings allowed Philip to use his great talent for networking and earn him many commissions, like that of Harry Selfridges’s unrealised Selfridges’s Tower and Hengistbury Castle, the construction for David Lloyd George of Bron-y-de and Chartwell for Sir Winston Churchill. The interwar years would be the peak of Philips career, working on country houses such as Cherkley Court for Lord Beaverbrook, Garsington Manor for Lady Ottoline Morell and Ramster Hall for Sir Henry Norman.

In 1935 Philip left London to settle in Devon. His career now in decline as fashions had started to change but he still continue working on prestigious country houses, with his final project being for himself. Sent in 1949 by the local council to assess Dunsland House, which had lain empty for several years, realising that no one else would step in to save this once grand building he purchased it and spent the last years of his life trying to restore it.

In 1935 Philip left London to settle in Devon. His career now in decline as fashions had started to change but he still continue working on prestigious country houses, with his final project being for himself. Sent in 1949 by the local council to assess Dunsland House, which had lain empty for several years, realising that no one else would step in to save this once grand building he purchased it and spent the last years of his life trying to restore it.

Philip's last act of notoriety was the publishing of his autobiography “True Remembrances: The Memoirs of an Architect” in 1954. So fantastic was the list of names, the accounts of parties and the like in this book that some would call it “dubious” and “unrealiable”. However it remains as his written account of one of the most artistically creative periods in British history.

Having lived in a time when homosexuality was illegal in Britain, Philip's sexuality had worn heavily on him and his health, he died in 1956 aged 69, having not managed to complete Dunsland House.

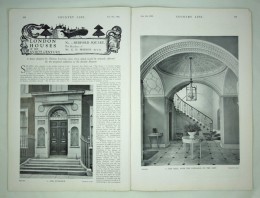

Although not considered a great architect, even attracting criticism from his contemporary Sir Edwin Lutyens, who after seeing some of his additions is quoted as saying “work so ill-conceived by a man who claims a following and dares to criticise”. Philip was a master of networking and inspiring confidence in his abilities to his clients. R. Randal Phillips writes on the decoration of No. 3 Pelham Crescent in South Kensington 'Mr Tilden has a particular gift for the decorative side of architecture, and is himself a brilliant draughtsman and colourist'.

Although not considered a great architect, even attracting criticism from his contemporary Sir Edwin Lutyens, who after seeing some of his additions is quoted as saying “work so ill-conceived by a man who claims a following and dares to criticise”. Philip was a master of networking and inspiring confidence in his abilities to his clients. R. Randal Phillips writes on the decoration of No. 3 Pelham Crescent in South Kensington 'Mr Tilden has a particular gift for the decorative side of architecture, and is himself a brilliant draughtsman and colourist'.

Philip Tilden's powerful imagination together with a deep sympathy for the historic buildings of England confirmed he would remain “the architect” for high society spanning three decades.

Bron-y-de, The Property of The Right Hon. D. Lloyd George. Designed by Phillip Tilden

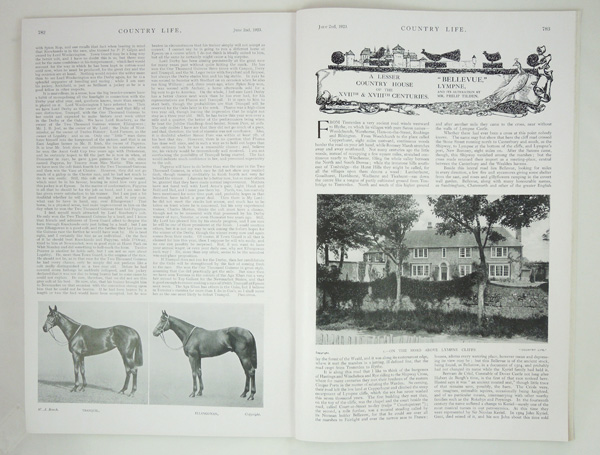

Port Lympne (Part 1) The Residence of Sir Philip Sassoon

Trent Park (Part-1), The Property of Sir Philip Sassoon, Bt