Richard Norman Shaw (1831-1912)

Born in Edinburgh, where Norman Shaw spent the first 15 years of his life before his family relocated to London. These early years had been filled with loss as his father died when Shaw was just two years old and three of his siblings would also die leaving his family dependant on his elder brother Richard who had moved to London to find work.

Soon after also moving to London, Norman Shaw began his apprenticeship with William Burn, which is when he would meet and become friends with the man whom he would form his first partnership with, William Eden Nesfield. During his apprenticeship Shaw attend lectures at the Royal Academy of Arts and eventually win a Traveling Scholarship from the Academy in 1854 after winning successive silver and gold medals. This association with the RA is where he would be noticed by the artist John Horsley RA, who recognised his talent and gave Shaw his first true commission.

In 1863 Shaw started his practice with Nesfield and Horsley commissioned Shaw to remodel his newly acquired house Willesley in Cranbrook, Kent. As was the fashion at this time for artists to move from the smog leaden streets of London to quiet and now easily accessible countryside. Horsley chose the unspoilt Kentish countryside and purchased an 18th century house which he instantly wished to remodel and turned to Shaw for this work. Here Shaw would produce for the first time his “Old English” style which Horsley would in his memoirs refer to as “Shaw’s first domestic masterpiece”. Here Shaw re-introduced the inglenook to the Victorian world which would, through his and Nesfield works, see a great resurgence in popularity. However, his next commission is where he would unleash his full vision of “Old English”

In 1863 Shaw started his practice with Nesfield and Horsley commissioned Shaw to remodel his newly acquired house Willesley in Cranbrook, Kent. As was the fashion at this time for artists to move from the smog leaden streets of London to quiet and now easily accessible countryside. Horsley chose the unspoilt Kentish countryside and purchased an 18th century house which he instantly wished to remodel and turned to Shaw for this work. Here Shaw would produce for the first time his “Old English” style which Horsley would in his memoirs refer to as “Shaw’s first domestic masterpiece”. Here Shaw re-introduced the inglenook to the Victorian world which would, through his and Nesfield works, see a great resurgence in popularity. However, his next commission is where he would unleash his full vision of “Old English”

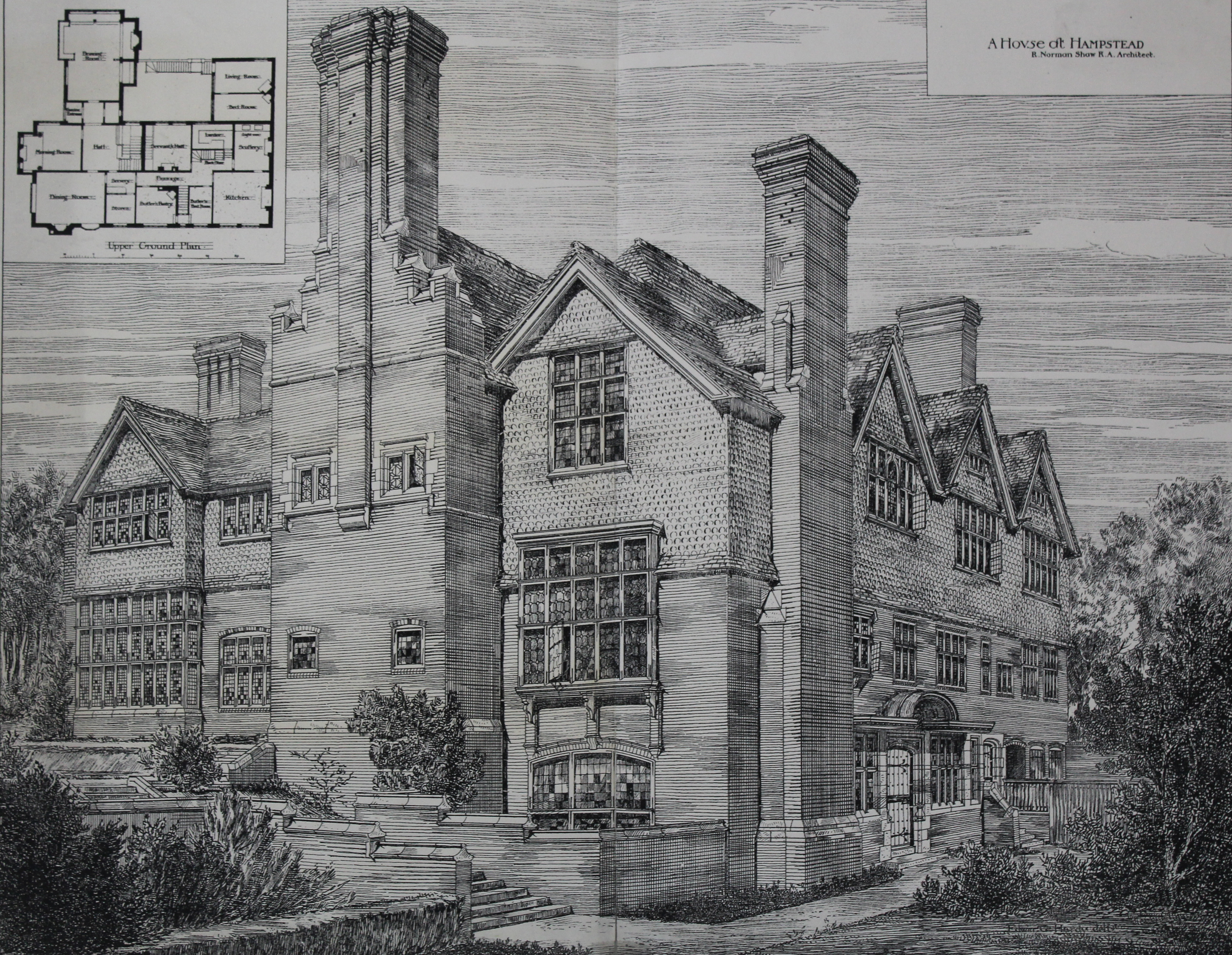

Another Royal Academician, E. W. Cooke employed him to build Glen Andred in Groomsbridge, Kent. Here, with a blank canvas Shaw created in the rocky landscape, a house with tall elegant chimneys, gable ends, vertical tiling, ornate plaster work and many other features that would be copied by lesser architects but also influence greats such as Edwin Luytens. Contemporaneously he would build Leyswood for his cousin James W Temple which would be described as a home that one could feel “like a squire in his manor”. From these two houses a flurry of commissions would follow including Grims Dyke in Harrow Weald that John Betjeman would attribute as being “a prototype of all the suburban houses in southern England”.

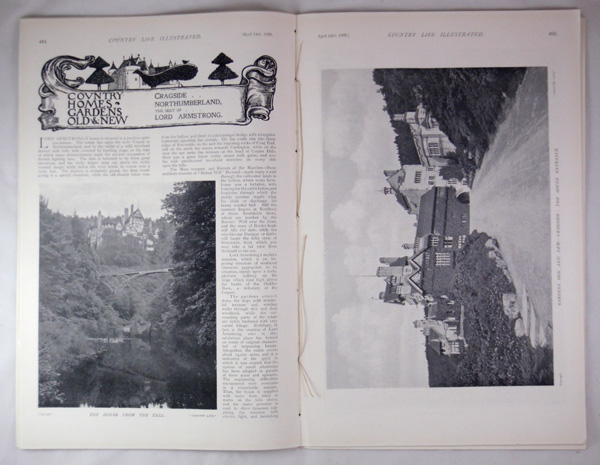

Straight after his Kentish creations were finished Shaw was contracted by Lord Armstrong to help create Cragside, the first house in the world to be electrified with its own hydroelectric plant. Armstrong wished to create a “future fairy palace” and it is reputed that Shaw sketched the design in a single afternoon whilst Armstrong was out shooting. This rambling mansion would be under constant expansion and alteration for the next 15 years.

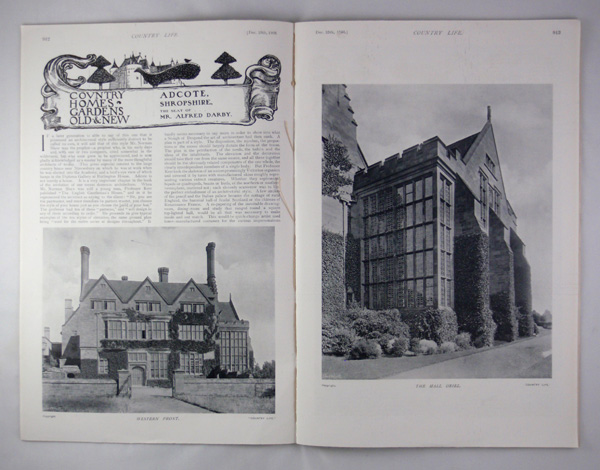

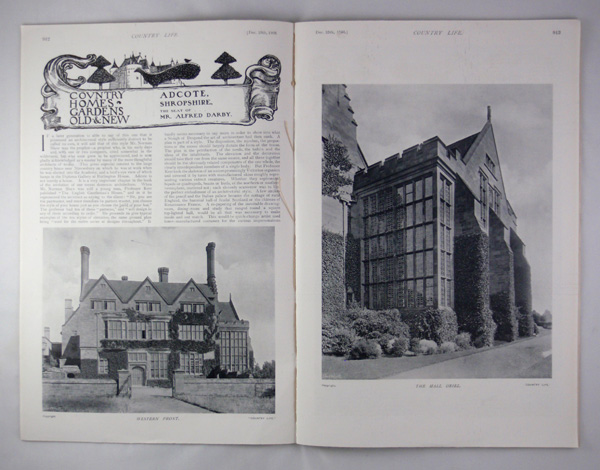

Shaw’s style would begin to change in the 1870’s as he moved away from half-timbered houses and more towards what would be later termed “Queen Ann Style” due to his drawing on influences from 17th century Flemish domestic design. During this decade Shaw would build for the Darby family in Little Ness, Shropshire, Adcote Hall which he would regard himself as his best country house. An autographed drawing done by Shaw of Adcote hangs in the Diploma Gallery at the Royal Academy of Arts today and is known as a masterpiece of architectonic drawing.

This period of Shaw’s career would see him construct buildings for some of the wealthiest individuals in England. Flete House in Devon would be altered for H.B. Mildmay of Barings Bank, Dawpool in Cheshire for Thomas Henry Ismay, owner of the White Star Line (the headquarters in Liverpool that Shaw would also design) and Bryanston in Dorset for Viscount Portman to name a few. Shaw would also design New Scotland Yard (now the Norman Shaw Buildings) which H.G. Wells would describe as “a fat beefeater of a policeman disguised miraculously as a Bastille”

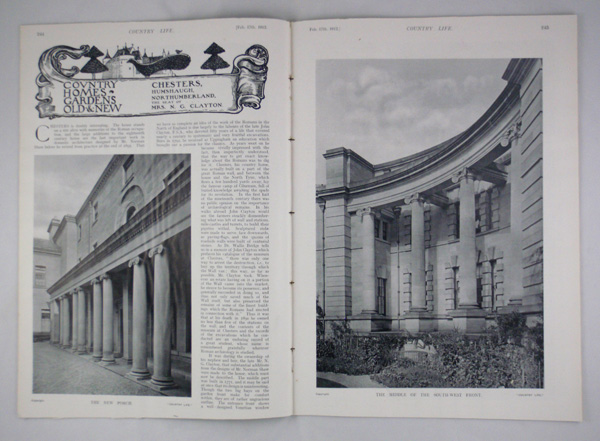

Shaw retired in 1895 after his remodelling of Chesters in Northumberland and was hailed at the time as the leading British architect. He continued to produce works for many years with among his last being The Dilly Hotel in Piccadilly.

Through-out his career Shaw adapted with changing fashions and publicised himself greatly with his use of magazines such as The Building News which assured him a place in the consciousness of those who wanted to have the latest styles and best architect of the time.

Through-out his career Shaw adapted with changing fashions and publicised himself greatly with his use of magazines such as The Building News which assured him a place in the consciousness of those who wanted to have the latest styles and best architect of the time.

With many examples of his architectural genius still standing today, his influence on the Arts and Crafts movement and involvement with projects such as Bedford Park in London, Richard Norman Shaw left a legacy that can be seen in leafy suburbs the world over not just in the grand manorial buildings of the late Victorian era.

Chesters, The Seat of Mrs N. G. Clayton

Cragside at Rothbury, The Seat of Lord Armstrong